Fictional science as economics

When you don't like the numbers... change them and wag the dog walker's leach. And if that doesn't work, make up something even more outrageous.

Uhoh... I made that mistake of checking the newsfeeds on a Monday morning....

So nothing else to do than to quickly summarize it into a sigh and a shrug and get on with whatever it is we're doing today right?

It's a good thing though, that I got reminded of a book I read a long time ago, and a scene in that which already perfectly summarized the news feed today for me... So I didn't have to pay that much attention to it anymore and was quickly able to forget it all again.

I'll share that scene from that book with you right here.

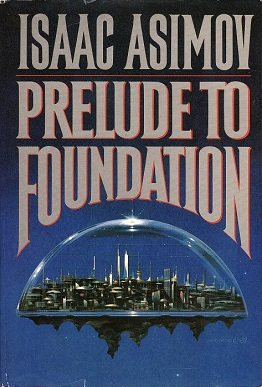

In 1998 , a nice book was published, which was pure science fiction.

It was one of those books about the future, with space travel and empires and things like that. It was called "Prelude to foundation" by Isaas Asimov.

But there's none of that space traveling sci-fi fantasy crap in this scene though. This is a simple scene where the emperor invites a math geek over for a "man to man" talk , because he heard that this math geek called Hari Seldon wrote a paper about what it means to predict the future and then apply that to an individual again.

Most of you are trying to make sense of things these days , I can tell. And understanding the mind of the emperor of the universe called Cleon can help with that right?

So here's that scene from Isaac Asimov's book from 1998... right smack before the .com bubble... remember that funny joke?

Anyways...

So the Emperor Cleon asks of Hari Seldon :

“Could not mind, as well as mindless motion, have an underlying order?”

“Perhaps. My mathematical analysis implies that order must underlie everything,

however disorderly it may appear to be, but it does not give any hint as to how this

underlying order may be found.

Consider Twenty-five million worlds, each with its overall characteristics and culture, each being significantly different from all the rest, each containing a billion or more human beings who each have an individual mind, and all the worlds interacting in innumerable ways and combinations! However theoretically

possible a psychohistorical analysis may be, it is not likely that it can be done in any practical sense.”

“What do you mean ‘psychohistorical’?”

“I refer to the theoretical assessment of probabilities concerning the future as

‘psychohistory.’ “

The Emperor rose to his feet suddenly, strode to the other end of the room, turned,

strode back, and stopped before the still-sitting Seldon.

“Stand up!” he commanded.

Seldon rose and looked up at the somewhat taller Emperor. He strove to keep his

gaze steady.

Cleon finally said, “This psychohistory of yours . . . if it could be made practical,

it would be of great use, would it not?”

“Of enormous use, obviously. To know what the future holds, in even the most

general and probabilistic way, would serve as a new and marvelous guide for our actions, one that humanity has never before had. But, of course--” He paused.

“Well?” said Cleon impatiently.

“Well, it would seem that, except for a few decision-makers, the results of

psychohistorical analysis would have to remain unknown to the public.”

“Unknown!” exclaimed Cleon with surprise.

“It’s clear. Let me try to explain.

If a psychohistorical analysis is made and the

results are then given to the public, the various emotions and reactions of humanity would at once be distorted.

The psychohistorical analysis, based on emotions and reactions that take place without knowledge of the future, become meaningless. Do you understand?”

The Emperor’s eyes brightened and he laughed aloud. “Wonderful!”

He clapped his hand on Seldon’s shoulder and Seldon staggered slightly under the

blow.

“Don’t you see, man?” said Cleon. “Don’t you see? There’s your use. You don’t

need to predict the future. Just choose a future--a good future, a useful future--and make the kind of prediction that will alter human emotions and reactions in such a way that the future you predicted will be brought about. Better to make a good future than predict a bad one.”

Seldon frowned. “I see what you mean, Sire, but that is equally impossible.”

“Impossible?”

“Well, at any rate, impractical. Don’t you see? If you can’t start with human

emotions and reactions and predict the future they will bring about, you can’t do the reverse either. You can’t start with a future and predict the human emotions and reactions that will bring it about.”

Cleon looked frustrated. His lips tightened.

“And your paper, then? . . . Is that what you call it, a paper? . . . Of what use is it?”

“It was merely a mathematical demonstration. It made a point of interest to

mathematicians, but there was no thought in my mind of its being useful in any way.”

“I find that disgusting, “ said Cleon angrily.

Seldon shrugged slightly.

More than ever, he knew he should never have given the paper.

What would become of him if the Emperor took it into his head that he had been made to play the fool?

And indeed, Cleon did not look as though he was very far from believing that.

“Nevertheless, “ he said, “what if you were to make predictions of the future,

mathematically justified or not; predictions that government officials, human beings whose expertise it is to know what the public is likely to do, will judge to be the kind that will bring about useful reactions?”

“Why would you need me to do that? The government officials could make those

predictions themselves and spare the middleman.”

“The government officials could not do so as effectively. Government officials do

make statements of the sort now and then. They are not necessarily believed.”

“Why would I be?”

“You are a mathematician. You would have calculated the future, not . . . not

intuited it--if that is a word.”

“But I would not have done so.”

“Who would know that?” Cleon watched him out of narrowed eyes.

There was a pause. Seldon felt trapped. If given a direct order by the Emperor,

would it be safe to refuse? If he refused, he might be imprisoned or executed. Not without trial, of course, but it is only with great difficulty that a trial can be made to go against the wishes of a heavy-handed officialdom, particularly one under the command of the Emperor of the vast Galactic Empire.

He said finally, “It wouldn’t work.”

“Why not?”

“If I were asked to predict vague generalities that could not possibly come to pass

until long after this generation and, perhaps, the next were dead, we might get away with it, but, on the other hand, the public would pay little attention.

They would not care about a glowing eventuality a century or two in the future.

“To attain results, “ Seldon went on, “I would have to predict matters of sharper

consequence, more immediate eventualities. Only to these would the public respond.

Sooner or later, though and probably sooner one of the eventualities would not come to pass and my usefulness would be ended at once. With that, your popularity might be gone, too, and, worst of all, there would be no further support for the development of psychohistory so that there would be no chance for any good to come of it if future improvements in mathematical insights help to make it move closer to the realm of practicality.”

Cleon threw himself into a chair and frowned at Seldon. “Is that all you

mathematicians can do? Insist on impossibilities?”

Seldon said with desperate softness, “It is you, Sire, who insist on

impossibilities.”

“Let me test you, man. Suppose I asked you to use your mathematics to tell me

whether I would some day be assassinated? What would you say?”

“My mathematical system would not give an answer to so specific a question,

even if psychohistory worked at its best. All the quantum mechanics in the world cannot make it possible to predict the behavior of one lone electron, only the average behavior of many.”

“You know your mathematics better than I do. Make an educated guess based on

it. Will I someday be assassinated?”

Seldon said softly, “You lay a trap for me, Sire. Either tell me what answer you

wish and I will give it to you or else give me free right to make what answer I wish

without punishment.”

“Speak as you will.”

“Your word of honor?”

“Do you want it an writing?” Cleon was sarcastic.

“Your spoken word of honor will be sufficient, “ said Seldon, his heart sinking,

for he was not certain it would be.

“You have my word of honor.”

“Then I can tell you that in the past four centuries nearly half the Emperors have

been assassinated, from which I conclude that the chances of your assassination are roughly one in two.”

“Any fool can give that answer, “ said Cleon with contempt. “It takes no

mathematician.”

“Yet I have told you several times that my mathematics is useless for practical

problems.”

“Can’t you even suppose that I learn the lessons that have been given me by my

unfortunate predecessors?”

Seldon took a deep breath and plunged in. “No, Sire. All history shows that we do

not learn from the lessons of the past. For instance, you have allowed me here in a private audience. What if it were in my mind to assassinate you? --Which it isn’t, Sire, “ he added hastily.

Cleon smiled without humor. “My man, you don’t take into account our

thoroughness--or advances in technology. We have studied your history, your complete record. When you arrived, you were scanned. Your expression and voiceprints were analyzed. We knew your emotional state in detail; we practically knew your thoughts.

Had there been the slightest doubt of your harmlessness, you would not have been

allowed near me. In fact, you would not now be alive.”

A wave of nausea swept through Seldon, but he continued.

“Outsiders have always found it difficult to get at Emperors, even with technology less advanced.

However, almost every assassination has been a palace coup.

It is those nearest the Emperor who are the greatest danger to him. Against that danger, the careful screening of outsiders is irrelevant. And as for your own officials, your own Guardsmen, your own intimates, you cannot treat them as you treat me.”

Cleon said, “I know that, too, and at least as well as you do. The answer is that I

treat those about me fairly and I give them no cause for resentment.”

“A foolish--” began Seldon, who then stopped in confusion.

“Go on, “ said Cleon angrily. “I have given you permission to speak freely. How

am I foolish?”

“The word slipped out, Sire. I meant ‘irrelevant.’

Your treatment of your

intimates is irrelevant. You must be suspicious; it would be inhuman not to be. A careless word, such as the one I used, a careless gesture, a doubtful expression and you must withdraw a bit with narrowed eyes. And any touch of suspicion sets in motion a vicious cycle. The intimate will sense and resent the suspicion and will develop a changed behavior, try as he might to avoid it.

You sense that and grow more suspicious and, in the end, either he is executed or you are assassinated. It is a process that has proved unavoidable for the Emperors of the past four centuries and it is but one sign of the increasing difficulty of conducting the affairs of the Empire.”

“Then nothing I can do will avoid assassination.”

“No, Sire, “ said Seldon, “but, on the other hand, you may prove fortunate.”

Cleon’s fingers were drumming on the arm of his chair.

He said harshly, “You are useless, man, and so is your psychohistory. Leave me.” And with those words, the Emperor looked away, suddenly seeming much older than his thirty-two years.

“I have said my mathematics would be useless to you, Sire. My profound

apologies.”

Seldon tried to bow but at some signal he did not see, two guards entered and took

him away. Cleon’s voice came after him from the royal chamber.

“Return that man to the place from which he was brought earlier.”

Don't forget though...

There is a way out of this madness and that's what all these other articles here are about.